Plant Trees

Give back to nature this Giving Tuesday - Plant a tree today!

About

Stay up to date on major announcements, exciting collaborations, and more. Visit our Newsroom

We make it simple for anyone to plant trees, and together we can make an incredible impact. Learn more

Stay up to date on major announcements, exciting collaborations, and more. Visit our Newsroom

We make it simple for anyone to plant trees, and together we can make an incredible impact. Learn more

Get Involved

Become a business partner to improve your company’s sustainability initiatives and make an impact. Learn more

See how your support and leadership can help us fund reforestation efforts across the globe. Learn more

Become a business partner to improve your company’s sustainability initiatives and make an impact. Learn more

See how your support and leadership can help us fund reforestation efforts across the globe. Learn more

Learn

Read about stories from the field, interesting facts about trees and get your healthy dose of nature. Visit our blog

Comprised of lesson plans, learning modules, resources, and activities, our T.R.E.E.S. School Program is the perfect addition to your curriculum. Learn more

Read about stories from the field, interesting facts about trees and get your healthy dose of nature. Visit our blog

Comprised of lesson plans, learning modules, resources, and activities, our T.R.E.E.S. School Program is the perfect addition to your curriculum. Learn more

Shop

Our fan-favorite Reforestation T-Shirt. Wear it with pride to show your support of reforesting our planet, one tree at a time. Shop now

Give the gift that lasts a lifetime! Choose an image, write your personalized message and select a delivery date to gift a tree. Gift a tree

Our fan-favorite Reforestation T-Shirt. Wear it with pride to show your support of reforesting our planet, one tree at a time. Shop now

Give the gift that lasts a lifetime! Choose an image, write your personalized message and select a delivery date to gift a tree. Gift a tree

Get Involved

Plant Trees

How Uniting Social and Environmental Justice Movements Can Create Real Change

Get news, updates, & event Info delivered right to your inbox:

How Uniting Social and Environmental Justice Movements Can Create Real Change

The current state of social unrest due to underlying issues of systemic racism, oppression, and violence against Black Americans and people of color is not typically an issue that One Tree Planted would address. But the intersection of social justice and environmental equity is undeniable - and we firmly believe that we must come together as a society in order to create a healthy, safe, and sustainable world for all.

How Did We Get Here?

What we’re hearing and seeing right now as it relates to theBlack Lives Matter movementmay feel overwhelming, but it's nothing compared to the lived experience of being black in America. And because people of color are also disproportionately affected by environmental injusticeslike polluted water supplies and hazardous waste dumps, we can see that even access to essential resources is not available to many.

The “mainstream” environmental movement has historically been criticized for being more focused on wilderness and wildlife than on human impacts. And it's probably true that when we think about the environment, buildings and sidewalks and busy roadways are not the first things that come to mind.

Unfortunately, for most of United States history, efforts to protect the environment have been exclusive, even leading to the deliberate placement of pollutants in black and poor communities of color. In contrast, the environmental justice movementtakes a broader view of the environment, including the places where we live, work, play, and learn — and aims to protect those that are most impacted by pollution.

What is Environmental Justice? A Response to Systemic Inequality and Injustice

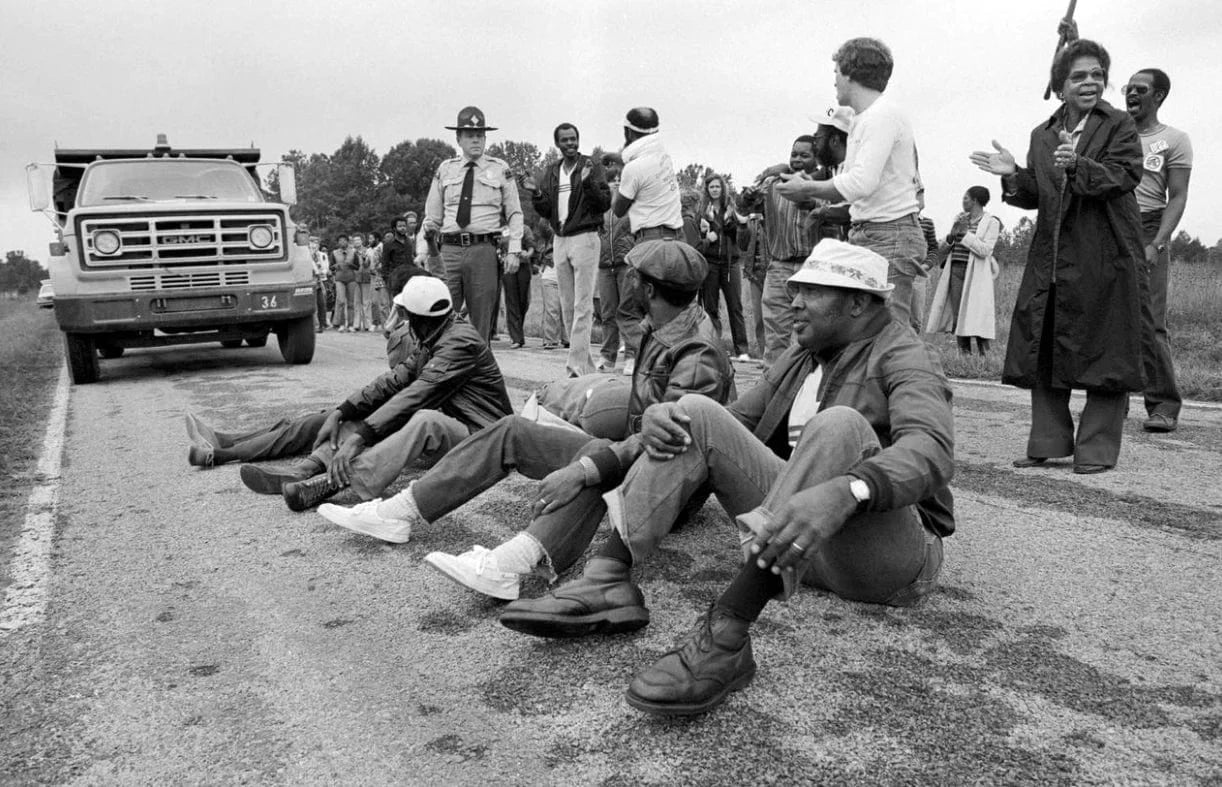

Many early leaders of the environmental justice movement were civil rights veterans, including Reverends Ben Chavis and Joseph Lowery, then of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and Reverend Leon White of the United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice. With them they brought tactics like marches, petitions, rallies, coalition building, community empowerment, education, litigation, and nonviolent direct action.

If this surprises you, it shouldn't. Pollution-producing facilities are most often sited next to poor communities of color. And rest assured, that is no accident. Corporate decision makers, regulatory agencies, and local planning and zoning boards have long known that it’s easier to site toxic facilities and waste dumps in these communities, than in middle-to-upper class white ones. That’s because poor communities and POC don’t have the same access to decision makers. Sometimes they don't even know they’re being poisoned — and when they do, they have a hard time fighting it without the prohibitively expensive technical and legal help required. Thanks to a lack of political power made worse by voter suppression, companies generally face lower transaction costs and fewer hurdles to getting permits — and are more able to influence local governments in their favor.

While some violence is overt and cause for immediate outrage, there is another type that is quieter, slower, without a clear enemy to blame yet that also takes away rights to life and livelihood.

The History Behind The Environmental Justice Movement

Most would agree that the environmental justice movement officially began in September of 1982, when the North Carolina government decided to dump 6,000 truckloads of PCB laced soil in the small, poor, and predominantly black town of Afton. A known carcinogen, PCBs can cause a laundry list of health and developmental problems — especially in children. They’re also incredibly persistent, and tend to bio-accumulate in the tissues of the organisms — including humans — that are exposed to them. Residents and their allies, deeply concerned about PCBs leaching into their drinking water supplies, bravely met the trucks, lying down on the roads that lead to the newly built landfill. Over 6 weeks of marches and nonviolent protests, more than 500 people were arrested and their cause received widespread national attention — and the PCBs got dumped anyway.

Over a decade later, on February 11, 1994, President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 12898, which mandated that federal government agencies take into account principles of environmental justice in their work. This was seen as a major win for the movement, but the work was not done.

While the Afton protests and Clinton's executive order really put environmental justice on the map, the struggle had hardly started there. In fact, at that point, American people of color had already been fighting against environmental injustice for decades. In the early 1960s, Cesar Chavez organized Latino farm workers to fight for workplace rights, including better protection from pesticide exposure in California’s farm fields. And in 1967, African American students took to the streets of Houston to protest a city dump in their community that had killed two children. Then, in 1986, West Harlem residents fought unsuccessfully against the installation of a sewage treatment plant in their community.

The Age-Old Story

It’s a story that’s older than time, and little has changed since the movement began. From Flint, MI to East Chicago, IN to Ringwood, NJ and the streets of Harlem, NY, the same story repeats itself: big interests target poor communities of color who, already oppressed by systemic racism and injustice, have a tough time fighting back. And the results are staggering.

According to a recent joint study by the NAACP and the Clean Air Task Force, which documented the high concentration of African Americans living near oil and natural gas facilities that release carcinogens:

- African Americans are exposed to 38% more polluted air than Caucasian Americans.

- African Americans are exposed to 38% more polluted air than Caucasian Americans.

- African Americans are 75% more likely to live in “fence-line” communities (communities that are next to a company, industrial, or service facility and are directly affected in some way by the facility’s operation).

- More than 1 million African Americans live within ½ mile of existing oil and gas facilities and more than 6.7 million live in counties with oil refineries.

- Many are particularly burdened with health impacts from this air pollution — which violates air quality standards — due to high levels of poverty and lack of health insurance.

- Approximately 13.4% of African American children have asthma (over 1.3 million children), compared to 7.3% for white children. They are also 10x more likely to die from it.

- Due to ozone increases resulting from natural gas emissions, children are burdened by 138,000 asthma attacks and 101,000 lost school days each year.

- Many also face an elevated risk of cancer due to toxic air emissions from natural gas development, with 1.1 million living in communities with emissions toxic enough to exceed the EPA’s level of concern for cancer risk

While these figures are heartbreaking, they represent just a small part of the picture. African American communities are also under constant assault from neighboring hazardous waste landfills, waste transfer stations, incinerators, garbage dumps, diesel bus and truck garages, auto body shops, smokestack industries, industrial hog and chicken processors, oil refineries, chemical manufacturers, and radioactive waste storage areas. It’s no surprise, then, that their cancer rates have historically been much higher than those of Caucasian communities.

Time For a Brighter Day

As you can see, environmental injustice is social injustice and should be recognized as such. As long as people of color continue to be exposed to disproportionate levels of pollution, we cannot fully address climate change or any other major environmental concern.

It is only by bringing the social and environmental justice movements together that we can begin to effect true change.

We need not only to stand in solidarity, but to actively work to bring about the long overdue systemic changes that this moment demands of us. That means supporting reforms that build communities socially, economically, and environmentally.

In the meantime, those of us that are white should take this time to step back, reflect on the role and deeply rooted psychology of racism, listen respectfully to what people of color have to say, amplify their message if given permission, support nonprofits and charities that support them, and to actively fight against racism any and every time we see it.

As the great Martin Luther King, Jr. once said:

“All life is interrelated. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality; tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly."And...

"We have flown the air like birds and swum the sea like fishes, but have yet to learn the simple act of walking the earth like brothers.”Within this crisis lies the opportunity to build a better world. So let's roll up our sleeves and get to work. Here are some organizations you can support to help the protests, and those dedicated to environmental justice.

Get news, updates, & event Info delivered right to your inbox:

Meaghan Weeden

Meaghan works to share our story far and wide, manages our blog calendar, coordinates with the team on projects + campaigns, and ensures our brand voice is reflected across channels. With a background in communications and an education in environmental conservation, she is passionate about leveraging her creativity to help the environment!

Related Posts

Real vs. Fake Christmas Trees: Which is Better For the Environment?

21/11/2023 by Meaghan Weeden

Green Friday: An Eco-Friendly Alternative to Black Friday

16/11/2023 by Gabrielle Clawson

Winter and Trees: How Do Trees Survive Winter?

14/11/2023 by Gabrielle Clawson

Popular On One Tree Planted

The 9 Oldest, Tallest, and Biggest Trees in the World

31/08/2023 by Meaghan Weeden

8 Amazing Bamboo Facts

18/07/2023 by Meaghan Weeden

Inspirational Quotes About Trees

11/07/2023 by Meaghan Weeden